Posted by lauraflynn on March 24, 2011 · Leave a Comment

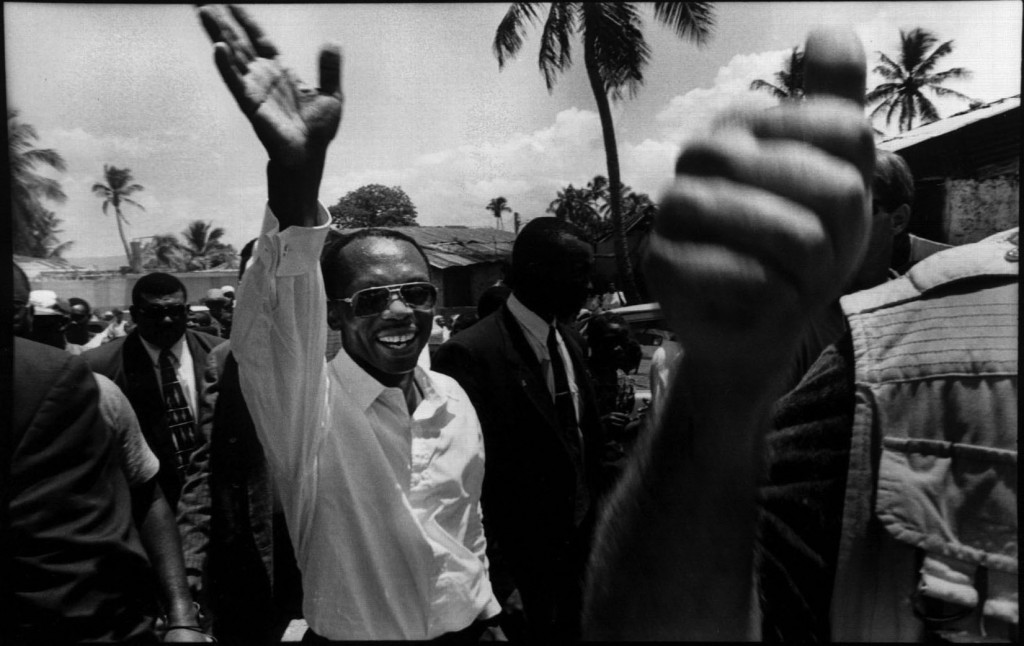

On March 18, 2011, former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide and his family returned to Haiti after seven years in exile. He was greeted at the airport by tens of thousands of Haitians who then accompanied him to his house in Tabarre. In an outpouring of unrestrainable joy, they made his house their own, as you can see from the photos here.

People in the courtyard of Aristide's house surrounding the car as he emerged. Photio Paul Burke

People welcoming Titid and his family at their house in Tabarre, photo Paul Burke

photo Paul Burke

From the airport just after he landed, Aristide addressed the Haitian people in a speech carried live on Haitian radio. He emphasized the need to move from a politics of exclusion to a one of inclusion of all social classes in the political, economic and social life of the nation. We reprint here the full text of speech as it was delivered primarily in Creole, with section in English, Spanish, Zulu, Swahili, and French.

Speech of Jean-Bertrand Aristide just after his arrival in Port-au-Prince, March 18, 2011

Sè m, Frè m, Onè ! Respè !

Otorite ki nan Leta Peyi d Ayiti,

Reprezantan Gouvènman Afrik Du Sud,

Anbasadè Matu ak Sè nou Matshidiso,

Otorite ki nan òganizasyon

Nasyonal kòm entènasyonal,

Sè m ak Frè m

Ki nan kat kwen peyi a ou aletranje,

Mwen kontan salye n nan lonbraj

Ayeropò Toussaint Louverture.

Sè m, Frè m,

Onè ! Respè !

Onè pou ou !

Respè pou Ayiti !

Ala kontan m kontan fè youn avèk

Minouche, Christine, Michaëlle pou

Salye ou e anbrase ou fratènèlman !

Sè m, Frè m,

Si w te ka poze men w sou kè mwen,

Ou ta santi kijan lap bat pi vit, pi plis

Pou di w : Bravo! Mèsi! Bravo! Mèsi!

Bravo pou kouraj ak entèlijans Pèp la !

Mèsi mil fwa pou akèy san parèy sa a !

Bravo pou tout bèl leson Pèp la deja bay !

Mèsi mil mil fwa pou bèl solèy solidarite

Ki pa te janm kouche dèyè mòn egzil sa a.

A warm welcome to :

Ira Kurzban, Dany Glover, Laura Flynn,

James Early, Selma James, widow of

CLR James, Margaret Prescod, Paul Burke.

Greetings to:

Honorable Deputy Maxine Waters,

Randall and Hezel Robinson,

Brian Cancanon, Claude Ribbe.

Peace to:

John Maxwell and the victims of

the disaster in Japan.

Onè ! Respè !

Onè pou ou e respè pou memwa

300.000 viktim tranbleman tè a !

Respè pou memwa tout moun ki

Viktim kolera ou katastwòf politik.

Men nan la men, bradsou bradsa,

Ann trese yon bèl kouwòn onè respè

Pou Rev Pè Gérard Jean-Juste ak

Tout lòt ewo ki sakrifye lavi yo nan

Defann diyite Ayiti ki malad grav.

Sè m, Frè m,

Pèmèt mwen pataje chalè remèsiman an

Ak anpil zanmi ki pa fèt an Ayiti, men

Ki renmen Pèp Ayisyen ak tout kè yo.

An 2004, gen nan yo ki te al chèche n

Nan peyi Afrik Santral pou akonpaye n

Rive nan peyi Jamayik an natandan

Prezidan Tabo Mbeki te chwazi depeche

Pwòp avyon prezidansyèl Lafrik Di Sid

Pou n te retounen nan bra manman Lafrik.

Yon gwo gwo mèsi pou Prezidan Zuma,

Prezidan Mbeki, Prezidan Mandela ak Tout lòt sè n ak frè n k ap viv nan peyi

Afrik Santral, Jamayik ak Afrik di Sid.

Jan m te di l, anvan n kite Afrik di Sid

Nan lang isiZoulou ak lang Swahili :

(IsiZoulou)

Yize iHaiti ikude naAfrika, asisoze sazikhohlwa

izimpande zamasiko ethu. Ngesikathi zonke

sizobatshela abantwana nezizukulu zethu :

Manikumbule lapho okoko bethu bazalelwe khona.

Niqubele ngokubona lendawo eya eAfrika.

Niqonde ngqo ngalo mgwaqo.

(Swahili)

Umoja ni nguvu,

Utengano ni udaifu.

Mtu ni watu.

Read more

Posted by lauraflynn on March 16, 2011 · Leave a Comment

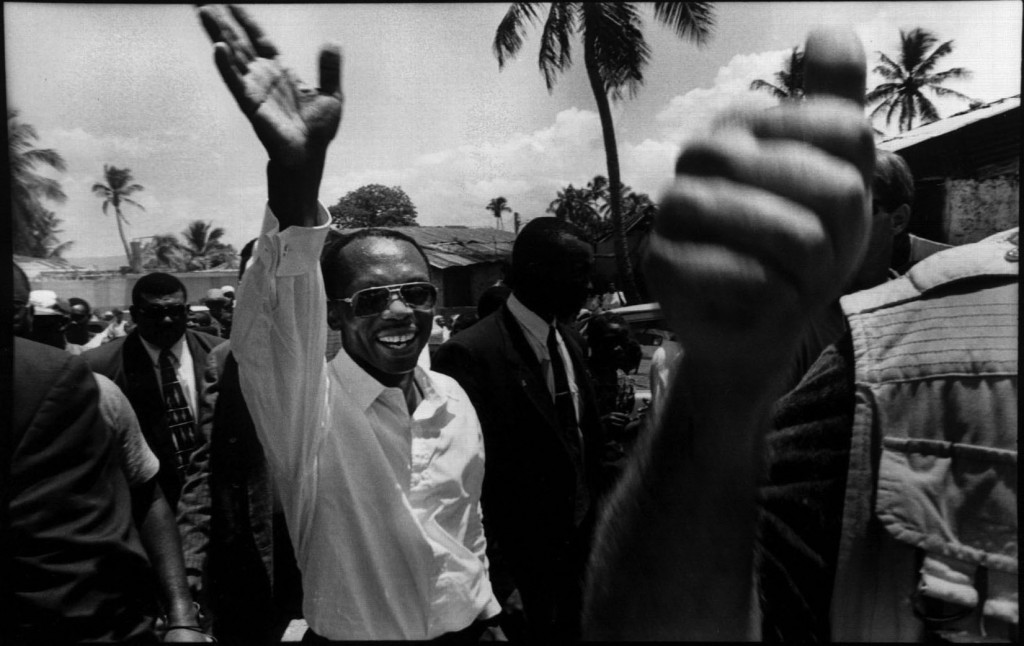

photo 1997©Jennifer Cheek Pantaléon

By Jean-Bertrand Aristide

Haiti’s devastating earthquake in January last year destroyed up to 5,000 schools and 80% of the country’s already weak university infrastructure. The primary school in Port-au-Prince that I attended as a small boy collapsed with more than 200 students inside. The weight of the state nursing school killed 150 future nurses. The state medical school was levelled. The exact number of students, teachers, professors, librarians, researchers, academics and administrators lost during those 65 seconds that irrevocably changed Haiti will never be known. But what we do know is that it cannot end there.

The exceptional resilience demonstrated by the Haitian people during and after the deadly earthquake reflects the intelligence and determination of parents, especially mothers, to keep their children alive and to give them a better future, and the eagerness of youth to learn – all this despite economic challenges, social barriers, political crisis, and psychological trauma. Even though their basic needs have increased exponentially, their readiness to learn is manifest. This natural thirst for education is the foundation for a successful learning process: what is freely learned is best learned.

Of course, learning is strengthened and solidified when it occurs in a safe, secure and normal environment. Hence our responsibility to promote social cohesion, democratic growth, sustainable development, self-determination; in short, the goals set forth for this new millennium. All of which represent steps towards a return to a better environment.

Education has been a top priority since the first Lavalas government – of which I was president – was sworn into officeunder Haiti’s amended democratic constitution on 7 February 1991 (and removed a few months later). More schools were built in the 10 years between 1994, when democracy was restored, and 2004 – when Haiti’s democracy was once again violated – than between 1804 to 1994: one hundred and ninety-five new primary schools and 104 new public high schools constructed and/or refurbished.

The 12 January earthquake largely spared the Foundation for Democracy I founded in 1996. Immediately following the quake, thousands accustomed to finding a democratic space to meet, debate and receive services, came seeking shelter and help. Haitian doctors who began their training at the foundation’s medical school rallied to organised clinics at the foundation and at tent camps across the capital. They continue to contribute tirelessly to the treatment of fellow Haitians who have been infected by cholera. Their presence is a pledge to reverse the dire ratio of one doctor for every 11,000 Haitians.

Youths, who through the years have participated in the foundation’s multiple literacy programmes, volunteered to operate mobile schools in these same tent camps. In partnership with a group from the University of Michigan in the US, post-traumatic counselling sessions were organised and university students trained to help themselves and to help fellow Haitians begin the long journey to healing. A year on, young people and students look to the foundation’s university to return to its educational vocation and help fill the gaping national hole left on the day the earth shook in Haiti.

Will the deepening destabilising political crisis in Haiti prevent students achieving academic success? I suppose most students, educators and parents are exhausted by the complexity of such a dramatic and painful crisis. But I am certain nothing can extinguish their collective thirst for education.

The renowned American poet and essayist, Ralph Waldo Emerson, wrote that “we learn geology the morning after the earthquake”. What we have learned in one long year of mourning after Haiti’s earthquake is that an exogenous plan of reconstruction – one that is profit-driven, exclusionary, conceived of and implemented by non-Haitians – cannot reconstruct Haiti. It is the solemn obligation of all Haitians to join in the reconstruction and to have a voice in the direction of the nation.

As I have not ceased to say since 29 February 2004, from exile in Central Africa, Jamaica and now South Africa, I will return to Haiti to the field I know best and love: education. We can only agree with the words of the great Nelson Mandela, that indeed education is a powerful weapon for changing the world.

(this piece was originally published in the Guardian on February 4, 2011, you can see the original here)

Posted by lauraflynn on January 26, 2011 · Leave a Comment

Published on the Huffington Post January 24, 2011, Commentary by AFD board menber, Laura Flynn

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/laura-flynn/not-even-the-past_b_813172.html

In Haiti, Reliving Duvalier, Waiting for Aristide

January 25, 2011

In the 1980s, when the armed forces of Jean-Claude Duvalier’s regime set about exterminating “Haiti’s Creole pigs”, they would come to Haiti’s rural villages, seize all of the “pigs”, pile them up, one on top of the other, in large pits and set fire to them, burning them alive.

A Haitian friend recounted this story to me this week. It was an image that she could not get out of her head since Jean-Claude Duvalier returned to Haiti. Because that’s what it was like for her, to watch Duvalier be greeted like a dignitary at the Port-au-Prince airport, and then escorted to his hotel by UN military forces — like being burned alive.

In 1968, when my friend was 3 years old, members of Duvalier’s Tonton Macoutes came to her home at 3 o’clock in the afternoon as her extended family shared a meal in the courtyard of their house in the Port-au-Prince neighborhood of Martissant. The Macoutes dragged her father and two of her uncles away. They then went to two other houses on her block, and took away all the men from those families as well. Her father and the other men in the neighborhood were members of MOP, the mass political party of Haitian populist leader Daniel Fignolé, which Duvalier wiped out, along with all other forces of opposition in the country.

None of the men taken from Martissant that day were ever seen again. They disappeared, perhaps perishing in the Duvaliers’ infamous prison, Fort Dimanche, after enduring torture, beatings, and starvation. The families could not even hold public funerals, and they never recovered the bodies of their loved ones. With the help of a sympathetic nun, my friend’s mother did manage a clandestine a mass for her husband, and later she consecrated an unmarked, empty tomb for him in Haiti’s National Cemetery. To this day, she visits that empty tomb on All Spirits Day each year to honor the husband she lost over 40 years ago.

The common wisdom, repeated endlessly in the international press since Duvalier’s return, is that Baby Doc’s regime was less repressive than his father’s. But my friend’s mother does not remember it that way. Left to raise six children on her own, she lived for nearly 20 years –until the fall of Baby Doc in 1986 — in constant terror that she or her children would be targeted again. Each day, the children rushed straight home from school and didn’t leave the house again. Each summer as soon as school ended, she packed them off to the countryside to breathe a sigh of relief.

Under Baby Doc the most spectacular violence, the murdering of whole families, mass purges of the military, and especially violence targeting Haiti’s wealthy families, abated. But the intimate terror the Duvalier regime exercised over every aspect of daily life continued. In Martissant, as in most Port-au-Prince neighborhoods, there were active members of the Macoutes in every other home. With almost unlimited power, they spied on and policed their neighbors, attacking, arresting, even killing people for such infractions as wearing an Afro, not wearing shoes, or leaving a light on after dark. Since the Macoutes were not formally paid, and since the economy was in a free fall, they enacted daily violence and extortion on the population to survive.

The children of those taken in Martissant that day in 1968 never forgot what happened to their fathers. As soon as they were old enough — just kids really, 12, 13 years old — they found themselves drawn into, and then propelling forward, a movement for change. Each Sunday morning, a chain of young people from Martissant set off across the city, jen pase pran jen, young people gathering more young people, until they numbered in the hundreds, arriving at doors of St. Jean Bosco in La Saline where a young priest was saying out loud what they had been saying in their hearts all their lives: Fok sa Chanje. This must change. These young people, joined by thousands of others in church and grassroots organizations across the country, ignited a movement that after long struggle and many lost lives, finally overthrew a 30-year dictatorship.

Read more

Next Page »